Parts of this piece were originally published in what would you cook for your younger self?, a lovely collective edition of Margaux Vialleron’s The Onion Papers.

I fill the pan with water about halfway, the blue one with the wooden handle. In the time it takes for water to boil, I start but don’t finish a number of small tasks: type an email, empty the dishwasher, refill the water bowl. When I hear a soft rumbling coming from behind me, I reach into the cupboard for the acid green plastic packet. I tear it open, drop the dried block into the gently boiling water. Lower the flame so the pot won’t boil over. Rip the seasoning packet and tip in the amount that feels right that day, usually ½ to ¾ the powdery contents. Sweep up the curled crumbs that didn’t make it into the water, scoop them into the packet, and tip them into the bin. I hear the dog padding over to the kitchen to hoover up any fallen tiny crispy segments. Swirl the water with chopsticks. Watch the block soften, begin to break apart.

I know it takes far less than 2 minutes and besides, time is reduced now to foaming starch and salt. I switch off the heat and reach for a deeper bowl, pulling the noodles as high as I can go into the air without them breaking. I know their texture intimately; I know the shape of their waves, how far they stretch. I know to plate up swiftly, not leaving them in their cooking water for too long or they’ll lose their bite. How long have I known this? Maybe for almost all time.

~ ~

We took the train five hours north, then drove a further three hours into the Highlands. Whenever I leave the city I bring a couple of packs of instant noodles with me. It’s a habit. I don’t even have them for breakfast that often back home, but instant noodles in the rural countryside seem to take on another level of pleasure.

I once found “instant biang biang mian”, a particular brand I’d never seen before (not in London, not anywhere) at the back of a small Sainsbury’s in the tiny student town of St. Andrews. It’s a truth universally acknowledged that wherever there are international students, the supermarket will have an interesting noodle selection. My parents were with us at the time; Mum and I marvelled at them. We ate some for a salty, spicy breakfast the next day. I bought three packs and took them back home to London with me.

I started noticing the gorse, bright clouds of blazing yellow all along the coastline. I’ve rarely been in Scotland in deep spring, and forgot about the gorse! I thought instantly of the hills above my parents’ house where, if you climb the zig-zag track high enough to reach the forested ridge, the bush gives way to an expanse of yellow gorse everywhere, all the way down to the sea where wind whips blue waves onto clusters of rocks against the road. When I turned my head and saw the headland and silvery expanse of water behind us I thought I was looking at a different landscape. I had to keep re-orientating myself.

The yellowness of the gorse took on a new level of intensity as we crossed the bridge to the Isle of Skye. We took our dog to a black sand beach and she skittered crazily around the rockpools, dried bits of seaweed getting caught in her hairy ears.

I spied something purplish blue and metallic on the shore. I went closer and saw that it was a giant jellyfish, distorted and warped from exposure to the wind and sun, melting on the rocks. The dog was near me, so I sort of shielded it from her with my body while also feigning disinterest so she wouldn’t go and shove her face into the desiccated jellyfish.

~ ~

When we were last in the Hebrides, back in 2021, there was a meal we ate in our car in a carpark overlooking the narrow stretch of water separating the Isle of Mull and the tiny Isle of Iona. It was from a shack that sold crabs, lobsters, oysters, freshly cooked with a side of fries and a wedge of lemon. My half lobster grilled in garlic butter felt like one of the best things I’d ever eaten in my life. I think it helps that that day we’d taken the ferry over to Iona and gone swimming twice in two different spots on the island, and spotted a seal floating on its back nearby. The combination of cold shock and bright sun had made us giddy. It was my first time going so far north. Despite the fresh seafood, after a few days of Scottish pub food I was craving noodles, chilli, ginger and fresh greens.

~ ~

When did I learn that instant noodles were “bad for you”? A better question: what meaning(s) do they hold in the different places I have lived? Here in the UK, as in Aotearoa, they are a symbol of cheap student meals: high salt, high calorie, MSG-infused, ultra-processed moral panic. For some, probably including me, an instant hit of nostalgia. But is a food nostalgic if you eat it every week?

Instant noodles as we know them today were invented in Japan, by Momofuku Ando of the company Nissin Foods. The wavy shape of the mass-produced noodle, pioneered by Nissin, allows for more elasticity, less slippage, and more noodles crammed into a packet. The bright fluorescent yellow of Maggi packets was the colour of my girlhood, always chicken flavour served in lightweight melamine bowls that remained oddly cool to the touch.

When we moved to China when I was a teenager, I discovered I was living in a city made of instant noodles. Shops, carts, trains, airports, planes full of noodle cups stacked high. Eaten on street corners, in corner shops, in offices, classrooms, on public transport. With melted cheese on top, as in Korean buldak ramen, or tossed with sweet soy sauce and fried pork chops in Shanghai iterations of Hong Kong cha chaan tengs.

What does it mean to label certain foods as “bad” and others “good”? How do these labels sit alongside histories of migration, intersections of class and race, the potency of nostalgia, and the pervasiveness of diet culture?

A single long noodle can be unravelled to reach across time and space in memory.

My relationship to my body is elastic, stretching tenderly into different shapes.

~ ~

A post on Instagram by the writer and academic Anna Sulan Masing, and her writing generally, reminds me to interrogate my nostalgia. This is something I am both failing and trying to do in my writing on food -- explorations (and sometimes, but not always, interrogations) of longing and belonging. When I flick through pages of my first prose book Tiny Moons I wonder if it’s overly steeped nostalgia, but it’s a true snapshot of a particular time in my life (early 20s) at an early point in my writing career. The poet Chen Chen taught me about looking back on your early work with kindness because it’s part of your younger self, another self. Feeling that distance only means you are changing and growing as an artist.

What makes instant noodles so bound up in longing and nostalgia for me? A childhood snack (but also somewhat acceptable in adulthood); a frequent and familiar constant when we were moving cities and moving houses; so easy to prepare that almost anyone could make them the way I liked them when I was very small, and later, I could learn to cook them myself at around the age of 14. A tenuous thread connecting to the Chinese side of my family and to my grandparents, where there was always a Maggi stash in the kitchen cupboard but Po Po made them slightly differently, in a good way.

If I’m keen to avoid ascribing morals to any kind of food, whether ultra-processed or not, why do I side-eye someone who might choose an acai bowl or green smoothie over a bowl of noodles for breakfast? Breakfast in particular (along with “morning routines” in general) feels bound up in our culture’s ideas about productivity, health, class and labour, to which we are all subject.

Recently, in a craft workshop, the chatter turned to breakfast. A woman across the table from me derided herself for having toast for breakfast that morning. “I know toast is bad,” she muttered, shaking her head in shame. How deep her shame went, it was hard to tell.

~ ~

Right now, in the depths of a big writing project, I can be lazy and ruthless with my cooking. Leftovers drizzled with chilli oil or (most often) a quick bowl of noodles with an egg on top. A list of instant noodle toppings I have loved:

kimchi

crispy fried shallots

chopped spring onions

chopped chives

a fried egg

a soft-boiled egg

shredded leftover roast chicken

gailan

cavolo nero

gem lettuce

tenderstem broccoli

chilli crisp

tofu puffs

tofu knots

silken tofu cut into cubes

I have something exciting to tell you!

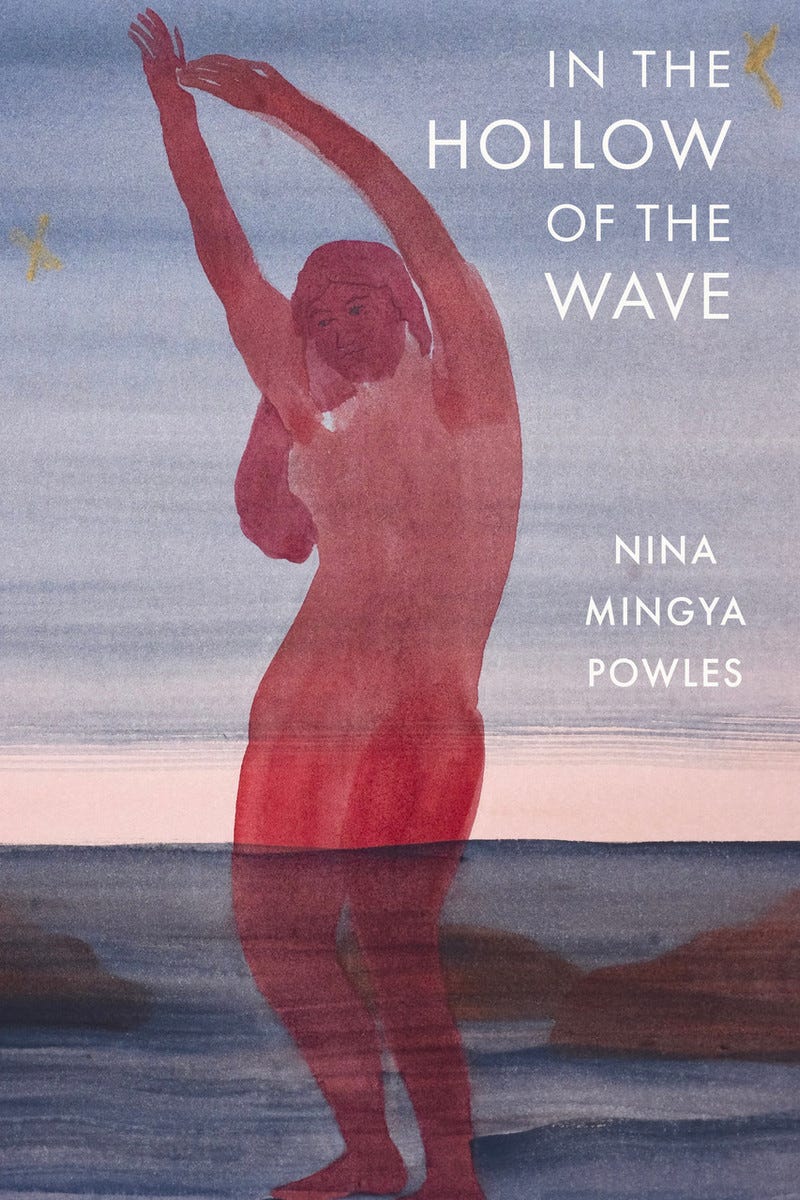

My next poetry collection, In the Hollow of the Wave, will be out in July 2025 and is available to pre-order from Nine Arches Press (UK) or Auckland Uni Press (NZ).

The beautiful artwork on the cover is by Bobbye Fermie.

Below, a small treat for paid subscribers —